Illegitimacy was not uncommon in earlier centuries. About 5% of all children born in England and Wales between 1837 and 1965 were illegitimate, which means they were born out of wedlock.

Many family tree researchers will find during their research that there is at least one illegitimate ancestor in their family.

Illegitimacy is no longer frowned upon like it was in the past, but finding that your ancestor was illegitimate may pose a problem when you conduct family tree research because it makes it that much more difficult to track down the name of the child’s father.

If you find there is a long gap between sibling’s birth dates, it is possible that the younger child may not be a brother or sister, but an illegitimate son or daughter of the supposed elder ‘sibling’, and passed off as being the child of the girl’s parents.

This brought great shame on the family, and they would go to any lengths to cover up the illegitimacy, even changing or falsifying records, which could pose problems for the family historian.

Although it can be upsetting to discover one of your ancestor’s may have been illegitimate, there can be reasons why this may have been the case, and the situation may not be because of promiscuity.

Certain reasons why the child may have been classed as illegitimate include prevention of a marriage in time, and the fact that the marriage may not have been recognised.

There are steps you can take to track down the father’s name which I discuss in detail below, which include perusing baptism registers, checking a child’s middle name, perusing army records, and checking census returns.

Circumstances May Have Prevented Parents Marrying Before Birth

Illegitimacy occurred in many walks of life.

It is possible that the couple had always intended to marry, but circumstances, such as the man being called into the army, or losing his livelihood so they could no longer afford to marry, precluded this from happening before the birth of the child.

In some circumstances, however, the man could have taken advantage of the woman, especially if they were in a servant-master relationship. Many unmarried mothers were domestic servants.

If women were unemployed, their desire to find a source of income could have led to them becoming prostitutes as a way of making ends meet. This, in turn, could lead to the woman discovering she was pregnant.

Marriage May Not Have Been Recognised

If your ancestor was deemed to be illegitimate, it may not mean that their parents were not married, just that the marriage was not recognised by the institution who recorded the birth.

If a marriage had taken place in a non-conformist church or chapel, it may not have been legitimate in the yes of the church, and thus treated accordingly.

If a man married the sister of his dead wife, the children were deemed to be illegitimate because the marriage was not considered to be valid.

Some Women Murdered Their Babies

To hide the shame of giving birth to an illegitimate child, some women murdered their babies to hide the fact. It is terrible that we once lived in a society where women felt compelled to take this drastic and devastating step.

Rights of Illegitimate Children

An illegitimate son of Royalty was not able to inherit his title from his father, but if the father recognised him as being his son, he may have been issued with a coat of arms, it being indicated that this line was illegitimate.

How to Find Father of Illegitimate Child – Steps You Can Take

Search Through Baptism Entries in Parish Registers

In earlier centuries, illegitimacy was considered sinful, and the clergyman could be most unfair to illegitimate children by writing the word ‘bastard’ after the entry in the baptism register. Some entries also state ‘base born’ or ‘natural’.

If a child was illegitimate, the entry in the parish register may simply state, as in the Courteenhall parish registers, Martha daughter of Sarah Dunckley (a bastard) baptised June 17, 1781, which does not help you to track down the child’s father.

It may be very difficult to prove who the father was under these circumstances.

Some entries in parish registers give much more information, however, such as this entry in the baptism register of Northampton St Giles: William Hartnell son of Mary Bason was born Nov 21 1764, and baptised Jun 26, 1765.

This could be as a reference to the name of the father, in this case William Hartnell or a member of the Hartnell family.

Some entries give you even more information, even stating the name of the reputed father, as in this entry from Northampton Holy Sepulchre: Ann bastard daughter of Jane Mickley baptised October 25, 1772; Charles Embery reputed father.

This information can give you another avenue to explore because this usually meant that this had been proven, or that he had admitted to being the father.

Father’s Name as Middle Name

It was not uncommon for the illegitimate child to have their possible father’s surname as a middle name, or to take the surname of their mother’s future husband, if she subsequently married, but it does not necessarily mean that this man was the child’s biological father.

Higher Rates of Illegitimacy in Towns in Earlier Centuries

The rate of illegitimacy was usually higher in the towns than in villages because women could have moved into the town looking for work, such as work as domestic servants.

If the woman was unable to make enough money through her job as a domestic servant, she made have turned to prostitution to make ends meet because no effective social welfare system existed.

More pressure was placed on couple’s in villages than in towns to marry before the child’s birth, hence you may find a baptism just a few weeks after the couple’s marriage.

It is also possible that the community were more likely to act adversely if the child was born as the result of a casual sexual encounter, rather than born to a couple married in all but name.

A woman having illegitimate children was more likely to bring shame on the family in the villages than in the towns because the village was a close-knit community.

A woman was not stigmatised in the same way in the towns, with this lack of shame encouraging illegitimacy. It was also easier for the woman to remain anonymous in the towns than in the villages.

Father May Have Been in the Army

One reason that a woman may have had an illegitimate child is that her partner was in the army, and had abandoned her after a casual sexual encounter.

Lord Strange was compelled to argue in a speech to parliament in 1750 that many redcoats behaved irresponsibly toward women and had no respect for marriage.

If you do find that the father was in the Army, it may well be worth investigating further to see if an army regiment was stationed nearby at the time that the woman may have become pregnant. This could lead you to discovering more about the man concerned, and possibly even his birthplace.

Family May Have Accepted the Illegitimate Child

If your ancestor had a illegitimate child, it does not necessarily follow that she was disowned by her family.

My ancestor, Maria Dunkley, had two illegitimate children in 1827 and 1835 respectively, the latter child, Isaac, living with his mother, grandfather John and uncle Benjamin in Roade, Northamptonshire in 1851.

This showed that the family had completely accepted Isaac into the family.

Isaac even eventually married Jane McJannett, the daughter of his elder brother William’s wife Ann McJannett, (who was also illegitimate, born to John Shingler) on 26 September 1864 in Courteenhall, Northamptonshire.

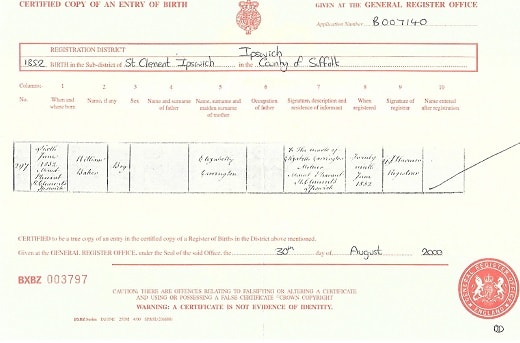

Birth and Marriage Certificates

After 1837, finding that no father is recorded on a birth certificate usually meant that the child was illegitimate, but could also have meant that the father did not register the birth and the official did not wish to put him on the birth certificate in these circumstances.

In these circumstances, the mother’s maiden name was stated on the certificate.

If you do not see the father’s name on a birth certificate, it is also worth checking to see if the child was baptised, because the entry in the baptism register could help you to determine if the child was indeed illegitimate.

This can cause a problem in family history research, but sometimes the registrar or clergyman would insist that the baby was given the father’s surname as a middle name.

Although this may not have been insisted upon by the clergyman, my illegitimate ancestor was named William Baker Carrington, subsequently changing his name to William Carrington Baker.

Although William was born on 6 June 1852, his parents did not marry until 27 March 1856. If you find your ancestor has a surname as a middle name, they could have been illegitimate, so if you are unable to find their birth registration, it is worth checking the index under their middle name as well.

When illegitimate children married, they did not always state their father’s name on a marriage certificate because they might not know it and also because the father might not have acknowledged their illegitimate child.

If the father was not stated on a marriage certificate, the bride or groom may have been illegitimate, but it could also simply mean that the father had disowned his child for some reason.

It is possible the bride or groom could simply make up a name, giving this fictitious man the same surname as themselves which can be very confusing when researching family history.

I have experience of this as my own relative, William Dunkley, stated Joseph Dunkley was his father when he married. Joseph was in fact his uncle.

If the events occurred after 1837, it is always worth obtaining both the birth and marriage certificates to prove or disprove your theory.

Illegitimacy Shown on the Census?

Sometimes, when looking at the ages of children born to the parents on a census, and the ages 20, 18, 15, 11 and 3 are shown, it is entirely possible that the 3 year old is in fact an illegitimate child of one of the elder siblings, so is in reality a grandchild rather than a child.

If your ancestor is living with a seemingly unmarried or widowed mother, as was the case for my own ancestor Mary Minton, who was living with her widowed? mother Mary in 1871, this could mean that the child may have been illegitimate.

If the census entry states that the mother was a widow, it is worth doing more research into whether or not she actually ever married, and was not stating that she was a widow to avoid awkward questions being asked.

Your Family May Know More About The Possible Illegitimacy

If the event occurred in within the lifetime of elder family members, they may be able to help you shed some light on whether your hunch is correct. If you take this path, however, please tread carefully because family members might find it difficult to discuss these events.

It is possible that the shame they felt at the time is still deeply felt. Do not be too disappointed if they are not prepared to divulge the information.

Definitive Proof Of Who The Father Was May Not be Forthcoming

It is entirely possible you will never be able to prove that a particular man is the child’s father, although you suspect that he was.

My ancestor, Maria Dunkley, had two illegitimate children William Campion Dunkley and Isaac Campion Dunkley in 1827 and 1835 respectively, them both being baptised with the middle name of Campion, leading me to believe that a Campion was my ancestor’s father.

Although there was a family of Campion’s in Roade, Northamptonshire at the time of the births, I have never been able to establish beyond reasonable doubt which Campion was the father.

Newspapers can Provide a Breakthrough

Sometimes, a breakthrough can come where you least expect it. My ancestor, Ann McJannett, had an illegitimate daughter Jane in 1846, but the child’s father was not mentioned on the birth certificate and the birth was registered under the mother’s name of McJannett.

Whilst looking in a newspaper, I came across Ann’s name with regard to this matter, and it turned out that Jane’s father was reported as being John Shingler. This proves how important newspapers are as a resource for tracing your family history.

The Child may have been Mentioned in a Will

If the father of the child was wealthy, he may have provided for the child in any possible will. This may help you to prove your suspicions.

Bastardy Bonds

From 1576, Justices of the Peace could track down the father of a bastard child and issue a bond known as a Bastardy Bond. Bastardy Bonds were issued by the parish against the father of an illegitimate child, so that they could ask him to reimburse the parish for any possible expense of looking after the child.

The child’s mother is named in the Bastardy Bond, it stating that she had sworn whilst under oath to a Justice of the Peace that she was with child and that the child was likely to be born a bastard and as such, chargeable to the parish.

The document was also signed by the father and their surety to show that they accepted the terms of the document so could not shirk their responsibilities. The father’s occupation was also mentioned in the bond, which may help you to ascertain if you have found the correct man.

The bastardy bond is useful to the family historian because the child’s father is usually named in the document, making it easier to ascertain if the mother of the child went on to marry the father of her child. This is especially useful if the name of the father was not mentioned in the baptism register.

Bastardy Bonds can be found in quarter sessions records. Please be aware, however, that not all illegitimate children were the subject of a bastardy bond because it was only issued if the child was likely to become chargeable to the parish.

A bastardy bond was also unlikely to be issued in the unhappy event that the child died and was buried a few days after being baptised. A wealthier woman may not appear in the bastardy bonds because she could make her own provision for her own bastard child.

An example of a bastardy bond from Barnwell St Andrew, Northamptonshire in 1772 states that ‘Ann Lane, singlewoman, hath declared that she is with child and that the child wherewith she goeth is likely to be born a bastard and to be chargeable to the said parish of Barnwell St Andrew and that Charles Kempston the younger the father of such child.’

Bastardy Examinations

The Bastardy Examination was conducted before two Justices of the Peace and enquired into the circumstances surrounding how the woman became pregnant. A woman had to attend a bastardy examination, but these usually occurred after the birth of the child.